MARKET CONDITIONS

Mark Whitmore explains, most investors steer clear of currency markets, thinking this market is for traders who must stay awake at all hours, keeping "one eye open," moving in and out of positions in the dead of night. He makes a compelling case instead for patient, long-term investment in currencies.

What makes Whitmore's article timely and thought provoking is the ongoing tug of war between inflation and deflation. Central banks around the world are desperate to spark some price inflation to help their debt-burdened governments and businesses. Printing more money makes existing money worth less and lessens the burden of debts owed.

It hasn't been so simple, though. While the Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan, and the European Central Bank buy debt securities and grow their balance sheets attempting to light inflationary fires, the velocity of money (GDP/M-2) and the money multiplier (M-2/monetary base) have slowed to a crawl.

In September of 2008, when the financial world crashed, velocity was 1.89 and the money multiplier was 8.61. Five years later, velocity is 1.54 and the money multiplier is 3.10. These are the lowest readings for either ratio since the Federal Reserve started keeping the relevant data.

While the tinder is there to create a hyperinflation brushfire, the still-crippled commercial banking industry isn't lending. So, money multiplication in the US is slow going. The other major central banks have had no better luck getting prices to move.

Whitmore has been investing currencies for decades. He is the chief executive officer of Whitmore Capital Management and manages Whitmore Capital, a currency-based hedge fund. As he illustrates in his piece below, there is a patient and disciplined approach to currency investing that can plug a hole in your portfolio diversification.

What makes Whitmore's article timely and thought provoking is the ongoing tug of war between inflation and deflation. Central banks around the world are desperate to spark some price inflation to help their debt-burdened governments and businesses. Printing more money makes existing money worth less and lessens the burden of debts owed.

It hasn't been so simple, though. While the Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan, and the European Central Bank buy debt securities and grow their balance sheets attempting to light inflationary fires, the velocity of money (GDP/M-2) and the money multiplier (M-2/monetary base) have slowed to a crawl.

In September of 2008, when the financial world crashed, velocity was 1.89 and the money multiplier was 8.61. Five years later, velocity is 1.54 and the money multiplier is 3.10. These are the lowest readings for either ratio since the Federal Reserve started keeping the relevant data.

While the tinder is there to create a hyperinflation brushfire, the still-crippled commercial banking industry isn't lending. So, money multiplication in the US is slow going. The other major central banks have had no better luck getting prices to move.

Whitmore has been investing currencies for decades. He is the chief executive officer of Whitmore Capital Management and manages Whitmore Capital, a currency-based hedge fund. As he illustrates in his piece below, there is a patient and disciplined approach to currency investing that can plug a hole in your portfolio diversification.

By Mark Whitmore, Whitmore Capital Management

Having primarily invested in currencies for over a decade now, both personally and recently as a fund manager, I do not think there is an asset class that is less understood. The most common misconception is that the currency markets are for traders, not investors. To be successful, one must sleep with "one eye open," nimbly entering and exiting positions throughout the day and night. I take the opposite view: Currency trading is at best an uphill battle, while currencyinvesting can provide investors superior opportunities for profit.

The Case for Currencies as an Asset Class

Some simply dismiss currencies as an asset class since all countries have fiat-based legal tender. The argument goes that since no currency is backed by gold or any other precious metal whose supply is constrained, all currencies are simply confetti—poised for debasement ad infinitum.

However, it does not follow that because fiat-based currencies are prone to debasement, they do not offer strong investment opportunities. What those who stress the perils of investing in paper currencies often fail to appreciate is this: The operative question should not be whether a particular currency is subject to debasement on an absolute basis, but instead whether a particular currency is more or less prone to debasement on a relative basis.

The modern era of untethered legal tender, beginning with Nixon abandoning the gold standard in 1971 and culminating in 2000 with Switzerland becoming the final nation to remove its currency from even being partially backed by gold, has created even greater investment opportunities in foreign exchange. Up until 2000, the range of central banking activities related to monetary expansion was much more limited, both in terms of qualitative policies and quantitative actions. Now, the disparities between the merely reckless central bankers and the central bankers who are reckless with extreme prejudice are made manifest.

Failing to appreciate the fact that significant disparities exist in the monetary policies of, and economic prospects for, different countries is to forgo the chance to potentially profit as future currency prices reflect those differences. To paraphrase Orwell, when it comes to investing in a world in which there is nothing but fiat money, while all currencies are equal, some currencies are more equal than others.

The standard case for including currencies as part of a diversified portfolio is twofold. First, currency investing has exhibited very low correlations to other asset classes, making it attractive for those looking to reduce portfolio volatility as well as potentially increase risk-adjusted returns. The second, more interesting, argument is that since a huge percentage of foreign exchange turnover comes from non-profit-seeking actors aiming to hedge currency exposure, market pricing may be prone to "inefficiencies" that can be exploited.

Personally, I think the latter argument mischaracterizes the potential profit opportunities the currency market offers. Perhaps the greatest debate in all of academic finance is whether it is possible to "beat the market" and generate positive alpha, or whether all such outperformance is explained by random distribution. Basically, the efficient market theorists and their ilk contend that markets factor in all relevant information in determining asset pricing. This means that the market price is the "right" price, making the expected profit of speculation into any given asset to be no greater than what the broader market for the asset itself would generate.

At least as it relates to currency markets, efficient-markets theorists are most certainly correct when it comes to the degree to which currency markets factor in virtually all relevant information, yet they may still be answering the wrong question. The key issue is not whether market pricing is the "right" price, but rather is it the right price for whom? I contend that foreign exchange markets have a persistent bias towards pricing that reflects almost exclusively the short-term prospects for currencies.

This presents currency investors with a longer time horizon the opportunity to take advantage of disparities between the current price of currencies and their fundamentally derived fair value, towards which currencies should gravitate over time.

Currency Strategies—One Tortoise for Every 220,000 Hares

Hedge funds and large commercial banks with proprietary currency desks have at their disposal virtually unlimited resources to expend in research and analysis. It would seem that an individual expecting to successfully "outmaneuver" these institutions when attempting to place currency trades would be a case study of hope triumphing over reason.

The evidence concerning retail currency trader track records would seem to confirm my suspicion that these traders are playing a game where the deck is stacked against them. The social network investing site eToro reports that about 90% of currency traders lose money.

Yet despite the obvious hurdles associated with currency trading, a large and growing percentage of the volume in the currency markets is from participants who anticipate holding their positions ephemerally. The Bank for International Settlements estimates that approximately 25% of all spot market volume in 2010 was from High Frequency Trading (HFT) sources, and that almost 80% of foreign exchange swaps were held for less than one week. The Aite Group estimates that by the end of 2012, HFT increased to 40% of spot market volume.

The structure of the futures market also manifests an extreme indifference among market participants towards longer-term investments in currencies. A review of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange data for August 2013 shows that of the $75,000,000+ in notational value of pound/yen (GBP/JPY) futures traded over a one-week period, not a single contract was bought or sold beyond September 2013. Even euro futures, the most popular and liquid currency future to trade, had less than 0.3% of its total futures contracts traded on August 13th go beyond one month out.

Shockingly, only one contract out of more than 220,000 euro futures that were traded that day extended into the first quarter of 2014!

Currency markets' pricing dynamics may thus offer long-term investors an advantage. After all, when it comes to having an edge against your competitors, it helps if they simply forfeit every game. With the vast prevalence of computers, money managers and individual traders making extremely short-term bets based upon non-fundamental factors, momentum and the reaction to "noise" are the chief determinants in the day-to-day pricing of currencies.

"Big picture" considerations that impact a currency's longer-term movements consistently fail to be reflected in market pricing. This creates fantastic opportunities for the handful of tortoises in the currency markets as they can bet against the momentum players who often push currency prices to unsustainable extremes.

A Model for Dynamic, Value-Based Currency Investing

If fiat-based currencies are actually a boon to investors, and currency markets can be profitably exploited in the longer term, what are the tools required for successful currency investing?

When I left the practice of law to pursue investing full-time in 2002, I was convinced there were huge opportunities for profiting in the currency markets if one employed a long-term, disciplined approach that was based on weighting macroeconomic variables and using regression analysis to somewhat frequently rebalance one's portfolio as prices and data constantly changed. Developing such a calculus became my passion and focus. While I have refined the model significantly over the years, its essential elements have remained unchanged.

What Benjamin Graham observed about the stock market is true a fortiori about the currency market: In the short run it is a voting machine, but in the long run it is a weighing machine. A wide variety of fundamental factors affect currency valuations. Personally I use roughly ten key macroeconomic variables, weighted based upon my observations on how significantly they impact currency prices over time. Perhaps the most intuitive and obvious is that of purchase power parity (PPP). Investors should select relevant macroeconomic variables by determining which ones, should they change, would make a currency more or less desirable to hold, ceteris paribus.

A critical element of my approach is dynamic scaling of positions. Once we can assess approximate fair values for currencies based upon their fundamentals, designing a currency investment portfolio becomes a matter of weighting most heavily those currencies that have the largest gaps between their market price and fair value. I take positions in no fewer than fifteen currencies, and usually closer to twenty, so as to ensure reasonably broad diversification.

Due to the fact that pricing in the currency markets can be quite fluid and dynamic, it is absolutely imperative that one somewhat frequently rebalance such a currency portfolio to reflect changes in pricing and even fair value. For instance, while the yen was Whitmore Capital's largest short one year ago, it is now not even one of the Fund's five largest shorts after its 20% decline in value versus the dollar.

Discipline and Patience

One of my favorite movies of the 90s is Bryan Singer's neo-noir thriller, The Usual Suspects. The film centers on an interrogation of Verbal Kint (played masterfully by Kevin Spacey) after he is witness to a port massacre. Eventually it is revealed that Keyser Söze, a criminal boss of almost mythical stature, is responsible. In detailing the unspeakably cruel and vicious things Söze had done over the years, Kint noted that Söze's great revelation was that, "To be in power, you didn't need guns or money or even numbers. You just needed the will to do what the other guy wouldn't."

While in a far more benign context, I find this observation to be extremely relevant to investing in foreign exchange markets: I am increasingly convinced that the most important characteristic a currency investor can possess if he hopes to achieve great success is the will to do the one thing that the money management industry and the vast majority of investors cannot countenance—lose money.

Inherent in the strategy I favor is the need to increase exposure to currency positions as they go against you. It requires discipline and patience, two things that most investors (and hence money managers who answer to them) have shown time and time again not to possess.

While seeing "cheap" currencies you own get cheaper (or having overvalued currencies you are short become even dearer in price) may seem unwelcome at the time, dollar-cost averaging into losing currency positions has proven to be the most profitable strategy I have employed throughout the years.

When the totality of fundamental factors for a particular currency is at extreme levels of overvaluation or undervaluation, I have found that price movement towards fair value is all but inevitable. But something being inevitable does not make it imminent. I see this as "when, not if" investing, but the question is whether an investor will have the stomach and the liquidity to weather what can be significant and seemingly interminable rallies in the other direction.

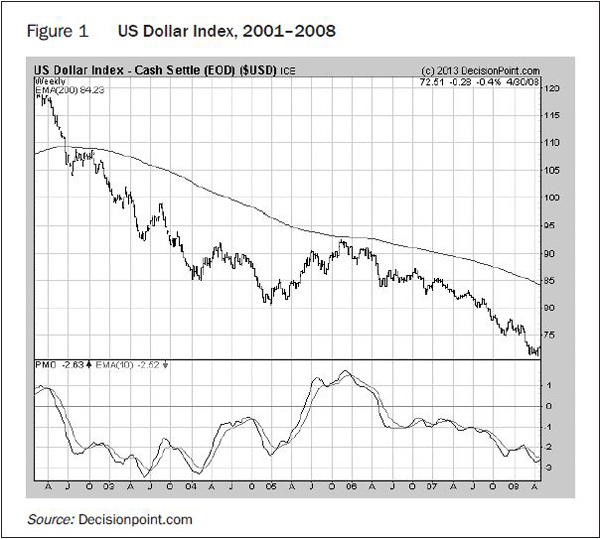

The importance of being willing to lose money in the short run to ultimately profit has been made clear to me on a repeated basis. Each of my most successful currency investments had either large initial losses or endured countertrend rallies that caused significant, but temporary, losses in the midst of a secular move. In one instance, the USD broadly increased in value more than 10% right in the midst of its 2001–2008 secular decline (see Figure 1).

Having primarily invested in currencies for over a decade now, both personally and recently as a fund manager, I do not think there is an asset class that is less understood. The most common misconception is that the currency markets are for traders, not investors. To be successful, one must sleep with "one eye open," nimbly entering and exiting positions throughout the day and night. I take the opposite view: Currency trading is at best an uphill battle, while currencyinvesting can provide investors superior opportunities for profit.

The Case for Currencies as an Asset Class

Some simply dismiss currencies as an asset class since all countries have fiat-based legal tender. The argument goes that since no currency is backed by gold or any other precious metal whose supply is constrained, all currencies are simply confetti—poised for debasement ad infinitum.

However, it does not follow that because fiat-based currencies are prone to debasement, they do not offer strong investment opportunities. What those who stress the perils of investing in paper currencies often fail to appreciate is this: The operative question should not be whether a particular currency is subject to debasement on an absolute basis, but instead whether a particular currency is more or less prone to debasement on a relative basis.

The modern era of untethered legal tender, beginning with Nixon abandoning the gold standard in 1971 and culminating in 2000 with Switzerland becoming the final nation to remove its currency from even being partially backed by gold, has created even greater investment opportunities in foreign exchange. Up until 2000, the range of central banking activities related to monetary expansion was much more limited, both in terms of qualitative policies and quantitative actions. Now, the disparities between the merely reckless central bankers and the central bankers who are reckless with extreme prejudice are made manifest.

Failing to appreciate the fact that significant disparities exist in the monetary policies of, and economic prospects for, different countries is to forgo the chance to potentially profit as future currency prices reflect those differences. To paraphrase Orwell, when it comes to investing in a world in which there is nothing but fiat money, while all currencies are equal, some currencies are more equal than others.

The standard case for including currencies as part of a diversified portfolio is twofold. First, currency investing has exhibited very low correlations to other asset classes, making it attractive for those looking to reduce portfolio volatility as well as potentially increase risk-adjusted returns. The second, more interesting, argument is that since a huge percentage of foreign exchange turnover comes from non-profit-seeking actors aiming to hedge currency exposure, market pricing may be prone to "inefficiencies" that can be exploited.

Personally, I think the latter argument mischaracterizes the potential profit opportunities the currency market offers. Perhaps the greatest debate in all of academic finance is whether it is possible to "beat the market" and generate positive alpha, or whether all such outperformance is explained by random distribution. Basically, the efficient market theorists and their ilk contend that markets factor in all relevant information in determining asset pricing. This means that the market price is the "right" price, making the expected profit of speculation into any given asset to be no greater than what the broader market for the asset itself would generate.

At least as it relates to currency markets, efficient-markets theorists are most certainly correct when it comes to the degree to which currency markets factor in virtually all relevant information, yet they may still be answering the wrong question. The key issue is not whether market pricing is the "right" price, but rather is it the right price for whom? I contend that foreign exchange markets have a persistent bias towards pricing that reflects almost exclusively the short-term prospects for currencies.

This presents currency investors with a longer time horizon the opportunity to take advantage of disparities between the current price of currencies and their fundamentally derived fair value, towards which currencies should gravitate over time.

Currency Strategies—One Tortoise for Every 220,000 Hares

Hedge funds and large commercial banks with proprietary currency desks have at their disposal virtually unlimited resources to expend in research and analysis. It would seem that an individual expecting to successfully "outmaneuver" these institutions when attempting to place currency trades would be a case study of hope triumphing over reason.

The evidence concerning retail currency trader track records would seem to confirm my suspicion that these traders are playing a game where the deck is stacked against them. The social network investing site eToro reports that about 90% of currency traders lose money.

Yet despite the obvious hurdles associated with currency trading, a large and growing percentage of the volume in the currency markets is from participants who anticipate holding their positions ephemerally. The Bank for International Settlements estimates that approximately 25% of all spot market volume in 2010 was from High Frequency Trading (HFT) sources, and that almost 80% of foreign exchange swaps were held for less than one week. The Aite Group estimates that by the end of 2012, HFT increased to 40% of spot market volume.

The structure of the futures market also manifests an extreme indifference among market participants towards longer-term investments in currencies. A review of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange data for August 2013 shows that of the $75,000,000+ in notational value of pound/yen (GBP/JPY) futures traded over a one-week period, not a single contract was bought or sold beyond September 2013. Even euro futures, the most popular and liquid currency future to trade, had less than 0.3% of its total futures contracts traded on August 13th go beyond one month out.

Shockingly, only one contract out of more than 220,000 euro futures that were traded that day extended into the first quarter of 2014!

Currency markets' pricing dynamics may thus offer long-term investors an advantage. After all, when it comes to having an edge against your competitors, it helps if they simply forfeit every game. With the vast prevalence of computers, money managers and individual traders making extremely short-term bets based upon non-fundamental factors, momentum and the reaction to "noise" are the chief determinants in the day-to-day pricing of currencies.

"Big picture" considerations that impact a currency's longer-term movements consistently fail to be reflected in market pricing. This creates fantastic opportunities for the handful of tortoises in the currency markets as they can bet against the momentum players who often push currency prices to unsustainable extremes.

A Model for Dynamic, Value-Based Currency Investing

If fiat-based currencies are actually a boon to investors, and currency markets can be profitably exploited in the longer term, what are the tools required for successful currency investing?

When I left the practice of law to pursue investing full-time in 2002, I was convinced there were huge opportunities for profiting in the currency markets if one employed a long-term, disciplined approach that was based on weighting macroeconomic variables and using regression analysis to somewhat frequently rebalance one's portfolio as prices and data constantly changed. Developing such a calculus became my passion and focus. While I have refined the model significantly over the years, its essential elements have remained unchanged.

What Benjamin Graham observed about the stock market is true a fortiori about the currency market: In the short run it is a voting machine, but in the long run it is a weighing machine. A wide variety of fundamental factors affect currency valuations. Personally I use roughly ten key macroeconomic variables, weighted based upon my observations on how significantly they impact currency prices over time. Perhaps the most intuitive and obvious is that of purchase power parity (PPP). Investors should select relevant macroeconomic variables by determining which ones, should they change, would make a currency more or less desirable to hold, ceteris paribus.

A critical element of my approach is dynamic scaling of positions. Once we can assess approximate fair values for currencies based upon their fundamentals, designing a currency investment portfolio becomes a matter of weighting most heavily those currencies that have the largest gaps between their market price and fair value. I take positions in no fewer than fifteen currencies, and usually closer to twenty, so as to ensure reasonably broad diversification.

Due to the fact that pricing in the currency markets can be quite fluid and dynamic, it is absolutely imperative that one somewhat frequently rebalance such a currency portfolio to reflect changes in pricing and even fair value. For instance, while the yen was Whitmore Capital's largest short one year ago, it is now not even one of the Fund's five largest shorts after its 20% decline in value versus the dollar.

Discipline and Patience

One of my favorite movies of the 90s is Bryan Singer's neo-noir thriller, The Usual Suspects. The film centers on an interrogation of Verbal Kint (played masterfully by Kevin Spacey) after he is witness to a port massacre. Eventually it is revealed that Keyser Söze, a criminal boss of almost mythical stature, is responsible. In detailing the unspeakably cruel and vicious things Söze had done over the years, Kint noted that Söze's great revelation was that, "To be in power, you didn't need guns or money or even numbers. You just needed the will to do what the other guy wouldn't."

While in a far more benign context, I find this observation to be extremely relevant to investing in foreign exchange markets: I am increasingly convinced that the most important characteristic a currency investor can possess if he hopes to achieve great success is the will to do the one thing that the money management industry and the vast majority of investors cannot countenance—lose money.

Inherent in the strategy I favor is the need to increase exposure to currency positions as they go against you. It requires discipline and patience, two things that most investors (and hence money managers who answer to them) have shown time and time again not to possess.

While seeing "cheap" currencies you own get cheaper (or having overvalued currencies you are short become even dearer in price) may seem unwelcome at the time, dollar-cost averaging into losing currency positions has proven to be the most profitable strategy I have employed throughout the years.

When the totality of fundamental factors for a particular currency is at extreme levels of overvaluation or undervaluation, I have found that price movement towards fair value is all but inevitable. But something being inevitable does not make it imminent. I see this as "when, not if" investing, but the question is whether an investor will have the stomach and the liquidity to weather what can be significant and seemingly interminable rallies in the other direction.

The importance of being willing to lose money in the short run to ultimately profit has been made clear to me on a repeated basis. Each of my most successful currency investments had either large initial losses or endured countertrend rallies that caused significant, but temporary, losses in the midst of a secular move. In one instance, the USD broadly increased in value more than 10% right in the midst of its 2001–2008 secular decline (see Figure 1).

Despite that, a disciplined, patient currency investor stood to profit nicely as the dollar declined more than 20% from its 2005 countertrend rally peak.

I cannot stress enough how investing in currencies is fundamentally different from trading them. Perhaps the most evident way in which they differ relates to the concept of discipline. In the trader's lexicon, the concept of discipline has a manifestly Orwellian doublespeak component. One is constantly encouraged to set tight stop-losses on orders, never letting losses "run."

From my experience, this is exactly the opposite behavior one would expect from a disciplined investing strategy. Indeed, using conventional trading discipline, I would have been stopped out of many of my short USD holdings in 2005, thus failing to maintain positions that were ultimately quite profitable.

Currency Opportunities Today

I am of the opinion we are in the most treacherous investing environment since the 1970s as the tug of war between inflation and deflation plays out in the global economy. While too vast of a topic to address here, in sum, we are left to consider the odds of what looks to be a distinctly bi-modal global economic future. It thus strikes me as prudent to execute currency investments in a manner so as to limit downside exposure in the event the world economy breaks in one direction or another.

Accordingly, my favored currency strategy at the moment is to find currency pairs whereby one is much more attractively priced than the other, yet both would move in a similar fashion no matter what the economic environment.

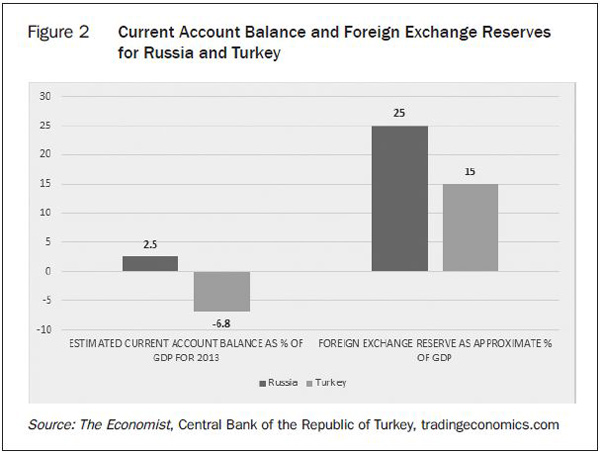

Both the Russian ruble (RUB) and the Turkish lire (TRY) have historically performed very poorly in financial downturns, and tend to appreciate when global economic complacency is high. But whereas Russia has almost no national debt (a pleasant result of going through a sovereign debt collapse, I suppose) and significantly positive current account balances, Turkey has about the worst current account balances of any country whose currency is significantly traded.

But Turkey's vulnerability to external financing shocks is even graver. As of July, Turkey's central bank reported its foreign reserves as a percentage of GDP stood at roughly 15%, putting Turkey in the lower ranks of emerging market nations. By way of comparison, Russia's foreign reserves as a percentage of GDP is 65% higher, coming in at approximately 25% (see Figure 2).

I cannot stress enough how investing in currencies is fundamentally different from trading them. Perhaps the most evident way in which they differ relates to the concept of discipline. In the trader's lexicon, the concept of discipline has a manifestly Orwellian doublespeak component. One is constantly encouraged to set tight stop-losses on orders, never letting losses "run."

From my experience, this is exactly the opposite behavior one would expect from a disciplined investing strategy. Indeed, using conventional trading discipline, I would have been stopped out of many of my short USD holdings in 2005, thus failing to maintain positions that were ultimately quite profitable.

Currency Opportunities Today

I am of the opinion we are in the most treacherous investing environment since the 1970s as the tug of war between inflation and deflation plays out in the global economy. While too vast of a topic to address here, in sum, we are left to consider the odds of what looks to be a distinctly bi-modal global economic future. It thus strikes me as prudent to execute currency investments in a manner so as to limit downside exposure in the event the world economy breaks in one direction or another.

Accordingly, my favored currency strategy at the moment is to find currency pairs whereby one is much more attractively priced than the other, yet both would move in a similar fashion no matter what the economic environment.

Both the Russian ruble (RUB) and the Turkish lire (TRY) have historically performed very poorly in financial downturns, and tend to appreciate when global economic complacency is high. But whereas Russia has almost no national debt (a pleasant result of going through a sovereign debt collapse, I suppose) and significantly positive current account balances, Turkey has about the worst current account balances of any country whose currency is significantly traded.

But Turkey's vulnerability to external financing shocks is even graver. As of July, Turkey's central bank reported its foreign reserves as a percentage of GDP stood at roughly 15%, putting Turkey in the lower ranks of emerging market nations. By way of comparison, Russia's foreign reserves as a percentage of GDP is 65% higher, coming in at approximately 25% (see Figure 2).

Other fundamental factors favor the ruble as well. Whereas Russia has a marginally positive real interbank interest rate level, inflation in Turkey exceeds its interbank interest rate by a substantial 4%. Finally, on a PPP basis, Turkey is shockingly expensive, particularly if one properly adjusts for standards of living. While Moscow is ridiculously expensive, prices in most other places in Russia are quite attractive. Thus RUB/TRY positions should appreciate in any economic environment in the medium to long term, with the RUB declining less than the TRY if markets are down, and the RUB increasing more than the TRY should markets continue to appreciate.

Another pair that appears to be a good risk-reward play is the Australian dollar (AUD)/New Zealand dollar (NZD). The NZD looks to be the most vulnerable to a significant correction among the dollar-bloc currencies. Its current account deficit as a portion of GDP is approaching 5%, while Australia recently reported a yearly current account deficit at less than 3.2%. Should asset markets become roiled once again, this level of a structural deficit in New Zealand's current accounts could be seen as an acute vulnerability.

Moreover, when adjusting for wage inputs, the NZD looks even more overvalued than the AUD on a PPP basis. The NZD is also still trading very near its all-time highs versus the dollar, whereas the AUD has recently pulled back more than 15% from its all-time USD highs. As a contrarian, I like the fact that the AUD is utterly despised. (In August, non-commercial traders had the largest net short position against the AUD in years.) Finally, should the precious metals complex eventually recover some, the AUD would be likely to get a little bit of a tailwind at its back compared to the NZD.

Given what I perceive to be a long history of foreign exchange markets offering relatively obvious opportunities for significant profit to the patient and disciplined investor, I am somewhat shocked that currencies continue to be almost completely overlooked as an asset class.

I just recently reviewed a model portfolio for high net worth individuals that had more than fifteen components. There was even 3% devoted to "trade finance receivables." Yet not a sliver was devoted to currency holdings.

I suspect that as a fund manager I will never have a plethora of competitors in the realm of longer-term currency investing. Nevertheless, for those investors willing to play a little outside the lines of traditional asset allocation, currency investing offers the opportunity to obtain both significant portfolio diversification and the prospect for excellent returns.

Another pair that appears to be a good risk-reward play is the Australian dollar (AUD)/New Zealand dollar (NZD). The NZD looks to be the most vulnerable to a significant correction among the dollar-bloc currencies. Its current account deficit as a portion of GDP is approaching 5%, while Australia recently reported a yearly current account deficit at less than 3.2%. Should asset markets become roiled once again, this level of a structural deficit in New Zealand's current accounts could be seen as an acute vulnerability.

Moreover, when adjusting for wage inputs, the NZD looks even more overvalued than the AUD on a PPP basis. The NZD is also still trading very near its all-time highs versus the dollar, whereas the AUD has recently pulled back more than 15% from its all-time USD highs. As a contrarian, I like the fact that the AUD is utterly despised. (In August, non-commercial traders had the largest net short position against the AUD in years.) Finally, should the precious metals complex eventually recover some, the AUD would be likely to get a little bit of a tailwind at its back compared to the NZD.

Given what I perceive to be a long history of foreign exchange markets offering relatively obvious opportunities for significant profit to the patient and disciplined investor, I am somewhat shocked that currencies continue to be almost completely overlooked as an asset class.

I just recently reviewed a model portfolio for high net worth individuals that had more than fifteen components. There was even 3% devoted to "trade finance receivables." Yet not a sliver was devoted to currency holdings.

I suspect that as a fund manager I will never have a plethora of competitors in the realm of longer-term currency investing. Nevertheless, for those investors willing to play a little outside the lines of traditional asset allocation, currency investing offers the opportunity to obtain both significant portfolio diversification and the prospect for excellent returns.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed