| RETIRE RICH Options as a investment strategy is the best hedge not only for your equities in your portfolio but also against inflation. Readers are familiar with my thoughts on the value of options and the article below will explain the benefits of using just one element of an options strategy to protect your positions. |

By Amber Lee Mason and Brian Hunt

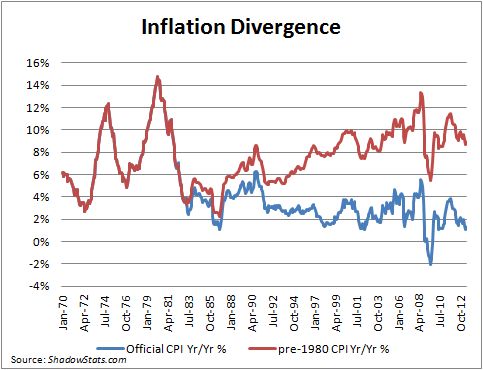

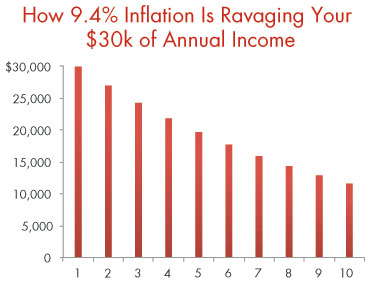

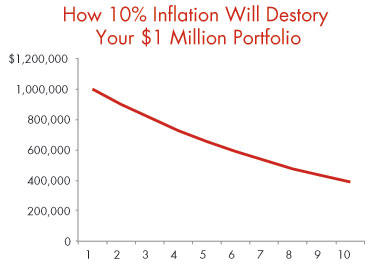

One of the biggest concerns we hear is: If the U.S. government is hell-bent on destroying the value of the dollar, how do I protect myself?

In a world of 0% interest rates on savings accounts and ultra-low rates on Treasurys, it's hard to prevent your wealth from eroding away.

The answer is to find safe, alternative sources of higher income. That could mean getting a raise at work... starting a new business... collecting tax-free yields from municipal bonds... or using world-class businesses to produce 10%-20% yields every year.

You might think that's impossible... You might think you can only get double-digit yields from risky stocks. But we're earning that much or more on shares of Coke.

Coke is one of the world's greatest companies. It owns many of the world's most valuable and powerful brands. It has terrific profit margins and a history of relentless dividend growth. Today, it pays a 2.8% dividend yield. But if you use a strategy we've shared with our readers, you can multiply that income five times over. You can do it by selling covered calls.

If you haven't tried this strategy yet, keep reading... It's more than worth your time to understand the basics.

When you sell covered calls, you can collect cash upfront for agreeing to sell your shares for a higher price. You give up some of your potential capital gains for guaranteed income and added safety.

This practice isn't for gamblers reaching for the moon. This is for folks interested in a safe, double-digit annual income stream.

You can read more about how it works right here. But here's what the numbers look like with Coke...

Right now, you can buy Coke for just under $40 per share. You can then sell the March $40 calls for around $1. That produces an instant "yield" of 2.5%. That might not sound like much. But if you use this strategy for a year, the gains will add up.

The calls expire on March 21, 10 weeks from now. If the stock has moved higher by then, you sell your shares at $40. If the stock stays where it is or moves lower, you keep your shares; and you can sell another round of calls. Making this trade five times in a year will produce a 12.5% return.

Add in Coke's annual dividend, and you're collecting more than 15% on a world-class stock.

If you're worried about earning enough to beat inflation, an annual yield of 15% will more than do it.

That's why selling options on the world's best stocks is one of our top inflation-protection ideas for this year.

One of the biggest concerns we hear is: If the U.S. government is hell-bent on destroying the value of the dollar, how do I protect myself?

In a world of 0% interest rates on savings accounts and ultra-low rates on Treasurys, it's hard to prevent your wealth from eroding away.

The answer is to find safe, alternative sources of higher income. That could mean getting a raise at work... starting a new business... collecting tax-free yields from municipal bonds... or using world-class businesses to produce 10%-20% yields every year.

You might think that's impossible... You might think you can only get double-digit yields from risky stocks. But we're earning that much or more on shares of Coke.

Coke is one of the world's greatest companies. It owns many of the world's most valuable and powerful brands. It has terrific profit margins and a history of relentless dividend growth. Today, it pays a 2.8% dividend yield. But if you use a strategy we've shared with our readers, you can multiply that income five times over. You can do it by selling covered calls.

If you haven't tried this strategy yet, keep reading... It's more than worth your time to understand the basics.

When you sell covered calls, you can collect cash upfront for agreeing to sell your shares for a higher price. You give up some of your potential capital gains for guaranteed income and added safety.

This practice isn't for gamblers reaching for the moon. This is for folks interested in a safe, double-digit annual income stream.

You can read more about how it works right here. But here's what the numbers look like with Coke...

Right now, you can buy Coke for just under $40 per share. You can then sell the March $40 calls for around $1. That produces an instant "yield" of 2.5%. That might not sound like much. But if you use this strategy for a year, the gains will add up.

The calls expire on March 21, 10 weeks from now. If the stock has moved higher by then, you sell your shares at $40. If the stock stays where it is or moves lower, you keep your shares; and you can sell another round of calls. Making this trade five times in a year will produce a 12.5% return.

Add in Coke's annual dividend, and you're collecting more than 15% on a world-class stock.

If you're worried about earning enough to beat inflation, an annual yield of 15% will more than do it.

That's why selling options on the world's best stocks is one of our top inflation-protection ideas for this year.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed