When you hear about the "gold reserves" a mining company has in the ground, the natural assumption would be that they're talking about a fixed number of ounces. After all, gold doesn't decay, and neither does it grow legs and move someplace else.

But assumptions are dangerous. In fact, industry-wide, reserves are likely to fall fairly significantly in the near future.

When the gold price falls, it doesn't just have a short-term impact on producers—slashed earnings and forced write-downs—it can affect the number of economically mineable ounces a company carries on its books, or even what it can mine in the future.

The Bar Is Higher Reserves are determined by a combination of factors: mostly cutoff grades, metals price assumptions, and projected production costs. For example, based on a gold price of $1,500 per ounce, a project may have economic ore at a cutoff grade of 1 gram per tonne (g/t).

But with gold selling in the low $1,300s, that same deposit may now require a higher cutoff grade, say 1.5 g/t, because the revenue earned from mining ore at the previous cutoff would be lower than the cost to extract it—a strategy that, as we all know, doesn't make a great business plan.

What Was Once "Ore" Is Now Just Dirt Higher cutoff grades reduce the number of economic ounces available for mining, especially if the gold price doesn't recover for a period of time.

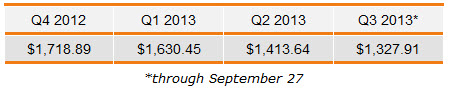

Here's the average gold price over the past four quarters:

This is the reason high-grade projects have better odds of survival than low-grade ones. Sure, all projects make less money when gold falls, but the higher-grade ones tend to have higher margins and see fewer slowdowns or shutdowns. In many cases, they still make great profits.

High Grading However, there's another phenomenon at work that will conspire to lower reserves: high grading.

Many projects have both low-grade and high-grade zones. When prices fall, a company can mine the richer ore and still make money. It may sound shortsighted, but it can be the right thing to do to stay profitable and be able to survive and advance in a temporarily weak price environment. But it does impact reserves, maybe more than you realize…

When metals prices are low and companies focus on high-grade ore, the low-grade material is temporarily bypassed. It's still physically there, but not only is it not economic at lower metals prices, it may never get mined at all.

That's because some low-grade ore only "works" when it's mixed with high-grade ore. Even when

gold moves back up to the price that the low-grade ore needed to be economic when mixed with the higher-grade ore, it doesn't matter, because the high-grade ore is gone. So it's not just gone legally, as

per regulatory definitions of mining reserves, it may be economically gone for good.

Miners could return to some of these zones in a very high gold price environment (something north of $2,000), but that's a concern for another day. The point for now is that many of today's low-grade zones can no longer be counted as reserves.

Now You See Them, Now You Don't Most companies update their reserves at year-end and report revisions in the first quarter. If gold doesn't stage a strong rebound soon, the industry will see a significant reduction in mineable reserves.

This will have repercussions on the precious metals sector, and on us as investors. As you might suspect, some of it is negative, but it also points to an investment opportunity that we believe will make us a lot of money.

Here's what Major Tom radios in about lower reserves and what that means to us investors…

- A corresponding decrease in the value of the company. A company with less product to sell won't be priced as high as it was previously. The exception here will be the producers that can maintain strong cash flow; those that do will be the ones that hold up the best.

- Watch out for companies that take a big write-down in reserves. Many producers will be forced to report lower reserves in early 2014 if gold prices stay where they are. But the Big Red Flags will be those with unusually large drops, because they may not have the reserves to keep production at the same level. These will mainly be the companies with low-margin projects, or those with low-grade material that will remain uneconomic because of high grading. If production falls, the stock will woo fewer investors.

- Lower reserves = lower supply = higher gold prices. Worldwide gold production is basically flat. If we see a substantial decrease in the number of ounces coming to market as a result of the fallout from reserve write-downs and demand stays at least where it is, prices will be forced up. This is already happening, but if it picks up steam, we could see a fire lit under gold prices.

- The better junior exploration companies could be big winners. Many producers, out of necessity, have reduced or even cut exploration budgets. Yet if they're going to survive, sooner or later they'll have to find more ounces. Every day a miner operates, his business gets smaller—but if he hasn't been exploring, the ounces won't be there when he needs them.

Even when gold prices return to prior highs, it will take years for large companies that have cut expenses to bring back all the laid-off geologists, identify and drill new deposits, and develop those that are economic.

There will only be one solution, and it will be a pressing one: buy an asset.

That's why right now is the best time to buy those juniors that have robust projects with strong economics. And I just bought one…

Casey Chief Metals Strategist Louis James recommended an advanced-stage gold exploration play in the current issue of the Casey International Speculator. The company has a large, high-grade deposit in Europe that looks poised to become much larger.

I plan to buy the best undervalued juniors now and be patient until the producers come a-calling. A monstrous run-up is coming in the junior sector, and all you have to do to profit is wait for the inevitable to arrive. Reserves are going lower, yes, but we'll be making some money.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed